I am fortunate to teach at Georgetown University, where bright and driven students continually motivate me to design entirely new courses - many among the first of their kind. These courses explore everything from early modern violence to the environmental challenges of the prehistoric world; from the history of attempts to explore and exploit Mars and the Moon to the reconstructed and projected consequences of global warming. Though their topics are diverse, all my courses rely on the core principles that inform my research. They combine humanistic and scientific disciplines; draw on diverse methods, sources, and perspectives; bridge huge divides in temporal and geographic scales; and offer new angles on today’s pressing challenges. The methods I use to put these principles into action emphasize diversity in class organization, active learning outside the classroom, and iterative learning in written assignments.

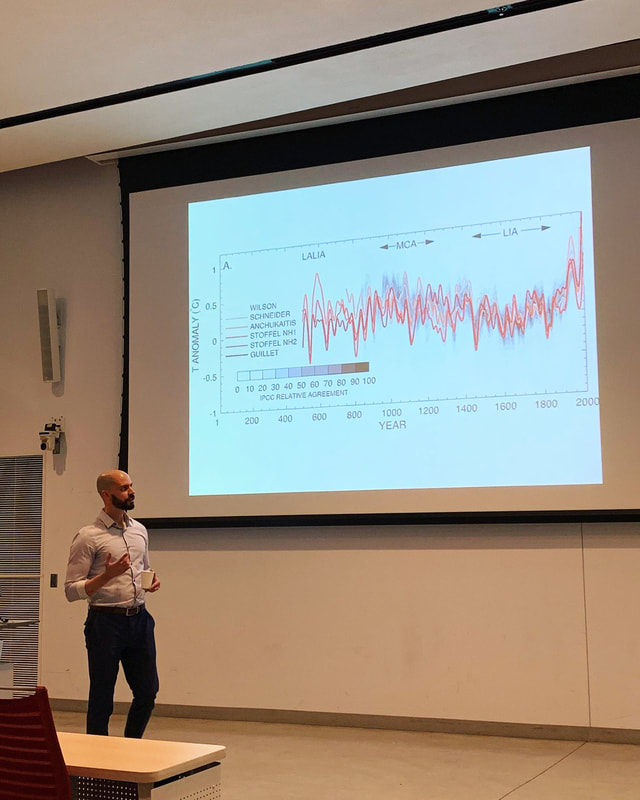

My environmental history courses trace reciprocal relationships between human or hominid communities and dynamic environments on timescales that range from a few centuries to millions of years. To unravel these relationships, students need to know how environments change, which means that they need to read articles in scientific disciplines that include climatology, ecology, geology, paleoclimatology, physics, and planetary science. Since few of my students have scientific training, I lead class discussions that teach students how to decode scholarship in unfamiliar disciplines. Through these discussions, students gain a basic scientific literacy that lets them discern the key findings of scientific articles and evaluate their significance.

After gaining an essential understanding of the Earth System (and in some courses the Solar System), students in my environmental history courses consider how human civilizations have evolved in ways that responded and contributed to environmental changes. To explore human history, students in my classes read books and articles in disciplines that include anthropology, archaeology, history (with its cultural, economic, environmental, gender, political, and military concentrations), and historical geography. I lead my students through discussions that consider how these disciplines construct and evaluate data to create knowledge about the human past.

Many of my lectures and class discussions integrate the methods, sources, and findings of humanists and scientists in case studies about distinct local or regional connections between environments and peoples. Students in my classes have considered, for example, the contested consequences of the Mount Toba eruption for hunter-gathers in Africa 75,000 years ago; the prehistoric destruction of megafauna in the Americas and Australasia; the complicated causes for the Neolithic emergence of agriculture in the fertile crescent; the scale of mining and pollution across the Roman Empire; the impact across Eurasia of volcanic eruptions in the sixth century CE; the effects of large-scale deforestation in high medieval Europe; the influence of climatic cooling on seventeenth-century rebellions; the discovery of the lunar environment at around the same time; the misinterpretation of Martian dust storms in the nineteenth century; the hypothesized emergence of the “Anthropocene;” and the likely contribution of global warming to instability in the modern Middle East. By teaching students how to read in different disciplines, I allow them to combine disciplinary perspectives in ways that introduce them to histories they have rarely – if ever – encountered before.

My environmental history courses trace reciprocal relationships between human or hominid communities and dynamic environments on timescales that range from a few centuries to millions of years. To unravel these relationships, students need to know how environments change, which means that they need to read articles in scientific disciplines that include climatology, ecology, geology, paleoclimatology, physics, and planetary science. Since few of my students have scientific training, I lead class discussions that teach students how to decode scholarship in unfamiliar disciplines. Through these discussions, students gain a basic scientific literacy that lets them discern the key findings of scientific articles and evaluate their significance.

After gaining an essential understanding of the Earth System (and in some courses the Solar System), students in my environmental history courses consider how human civilizations have evolved in ways that responded and contributed to environmental changes. To explore human history, students in my classes read books and articles in disciplines that include anthropology, archaeology, history (with its cultural, economic, environmental, gender, political, and military concentrations), and historical geography. I lead my students through discussions that consider how these disciplines construct and evaluate data to create knowledge about the human past.

Many of my lectures and class discussions integrate the methods, sources, and findings of humanists and scientists in case studies about distinct local or regional connections between environments and peoples. Students in my classes have considered, for example, the contested consequences of the Mount Toba eruption for hunter-gathers in Africa 75,000 years ago; the prehistoric destruction of megafauna in the Americas and Australasia; the complicated causes for the Neolithic emergence of agriculture in the fertile crescent; the scale of mining and pollution across the Roman Empire; the impact across Eurasia of volcanic eruptions in the sixth century CE; the effects of large-scale deforestation in high medieval Europe; the influence of climatic cooling on seventeenth-century rebellions; the discovery of the lunar environment at around the same time; the misinterpretation of Martian dust storms in the nineteenth century; the hypothesized emergence of the “Anthropocene;” and the likely contribution of global warming to instability in the modern Middle East. By teaching students how to read in different disciplines, I allow them to combine disciplinary perspectives in ways that introduce them to histories they have rarely – if ever – encountered before.

Students in my "Neighboring Worlds" and "Mars and the Moon" courses use telescopes to experience the Moon and planets.

My commitment to interdisciplinarity extends to written class assignments. First assignments in my courses usually encourage students to approach a case study in environmental history by finding and combining scholarship from different scientific and humanistic disciplines. Some of these assignments require students to use secondary sources to compose an original argument about a primary source, which can be anything from a sixteenth-century ship logbook to an internal memo recovered from the archives of a twentieth-century oil company.

Second assignments in my courses often require students to find their own primary sources on what they consider to be an especially interesting interaction between people and nature. I urge my students to develop an original argument that draws on their primary source and contextualizes it using secondary sources in different disciplines. I have organized library workshops that allowed my students to find a remarkable range of primary sources, from letters written by Carl Sagan and housed in the Library of Congress to chronicles composed in seventeenth-century France. Using these sources, students have written class essays on topics that include the impact of the Little Ice Age on the logistics of the eighteenth-century slave trade; the discovery of asteroids by nineteenth-century astronomers; the influence of climate change on the American Civil War; the consequences of severe El Niño events for military campaigns in nineteenth-century Patagonia; the intensification of American rubber production in the twentieth century; and the environmental history of U.S. military involvement in Afghanistan.

While writing such essays, many of my students have thought deeply about how environmental historians bridge events and trends on different temporal and geographic scales. They often had to wrestle with, for example, the occasionally counterintuitive consequences of climatic trends across short timeframes in local communities; or the impact of global commodity chains for military operations in local environments. Connecting trends and events on different scales led most of my students to a deeper awareness of the environmental challenges that confront humanity today.

I encourage such thinking by asking questions in class that explicitly challenge students to consider what environmental history can teach us about the present and the future. Students have debated, for example, what seventeenth-century episodes of social instability in the Little Ice Age can reveal about the future of conflict in a warmer world; what reactions to the supposed detection of Martian canals in the nineteenth century suggest about possible responses to the discovery of life beyond Earth; and what the success of the Montreal Protocol in preserving Earth’s essential ozone layer reveals about the likelihood that international treaties can effectively curb global warming. I emphasize that history can often provide fresh perspectives on issues that may shape the world into which my students will graduate.

My commitment to introducing my students to diverse disciplinary perspectives has also led me to experiment with different ways of structuring my classes. In smaller classes, I usually give short lectures to clarify key concepts, and then organize desks in a circle before beginning discussions that largely draw from weekly readings. In both larger and smaller classes, I often divide students into small groups and challenge them to use primary sources or digital tools that I provide for them to develop an argument that they must then present to the class. Groups in my classes have, for example, drawn on Machiavelli’s theories and a map I provided to plan an attack or defence of a sixteenth-century city. They have used interactive online maps to identify and explain features on the Moon and Mars. They have found examples of societal vulnerability, resilience, and adaptation to climate change in seventeenth-century paintings. They have interrogated readings about past relationships between climatic trends and conflict using a combination of NOAA’s “Climate Re-analyser” tool and detailed maps of the Middle East. They even learned the basics of Geographic Information System (GIS) software in order to trace the past impacts of climate change across the United States.

I have also “flipped” my classroom by recording podcast episodes for students to listen to at home. I then lead group readings in class of short articles that shed further light on issues discussed in these episodes. In some episodes, I interview the authors of required course books, who offer further insights on the themes in their books and the process of writing them. I have found that students – especially quieter students – respond energetically to activities that encourage them to approach topics in new ways.

Second assignments in my courses often require students to find their own primary sources on what they consider to be an especially interesting interaction between people and nature. I urge my students to develop an original argument that draws on their primary source and contextualizes it using secondary sources in different disciplines. I have organized library workshops that allowed my students to find a remarkable range of primary sources, from letters written by Carl Sagan and housed in the Library of Congress to chronicles composed in seventeenth-century France. Using these sources, students have written class essays on topics that include the impact of the Little Ice Age on the logistics of the eighteenth-century slave trade; the discovery of asteroids by nineteenth-century astronomers; the influence of climate change on the American Civil War; the consequences of severe El Niño events for military campaigns in nineteenth-century Patagonia; the intensification of American rubber production in the twentieth century; and the environmental history of U.S. military involvement in Afghanistan.

While writing such essays, many of my students have thought deeply about how environmental historians bridge events and trends on different temporal and geographic scales. They often had to wrestle with, for example, the occasionally counterintuitive consequences of climatic trends across short timeframes in local communities; or the impact of global commodity chains for military operations in local environments. Connecting trends and events on different scales led most of my students to a deeper awareness of the environmental challenges that confront humanity today.

I encourage such thinking by asking questions in class that explicitly challenge students to consider what environmental history can teach us about the present and the future. Students have debated, for example, what seventeenth-century episodes of social instability in the Little Ice Age can reveal about the future of conflict in a warmer world; what reactions to the supposed detection of Martian canals in the nineteenth century suggest about possible responses to the discovery of life beyond Earth; and what the success of the Montreal Protocol in preserving Earth’s essential ozone layer reveals about the likelihood that international treaties can effectively curb global warming. I emphasize that history can often provide fresh perspectives on issues that may shape the world into which my students will graduate.

My commitment to introducing my students to diverse disciplinary perspectives has also led me to experiment with different ways of structuring my classes. In smaller classes, I usually give short lectures to clarify key concepts, and then organize desks in a circle before beginning discussions that largely draw from weekly readings. In both larger and smaller classes, I often divide students into small groups and challenge them to use primary sources or digital tools that I provide for them to develop an argument that they must then present to the class. Groups in my classes have, for example, drawn on Machiavelli’s theories and a map I provided to plan an attack or defence of a sixteenth-century city. They have used interactive online maps to identify and explain features on the Moon and Mars. They have found examples of societal vulnerability, resilience, and adaptation to climate change in seventeenth-century paintings. They have interrogated readings about past relationships between climatic trends and conflict using a combination of NOAA’s “Climate Re-analyser” tool and detailed maps of the Middle East. They even learned the basics of Geographic Information System (GIS) software in order to trace the past impacts of climate change across the United States.

I have also “flipped” my classroom by recording podcast episodes for students to listen to at home. I then lead group readings in class of short articles that shed further light on issues discussed in these episodes. In some episodes, I interview the authors of required course books, who offer further insights on the themes in their books and the process of writing them. I have found that students – especially quieter students – respond energetically to activities that encourage them to approach topics in new ways.

With that in mind, I stress active learning outside of the classroom. In some of my courses, I ask students to find exhibits in local museums that shed light on topics in weekly readings. Every week, a different student in these courses gives a presentation about the exhibit and the perspectives it provides on our readings. In a course about the Anthropocene, I encouraged students to take pictures in or around Washington, DC. I then asked them to write a short assignment that explains what those pictures reveal about local relationships between people and environments. In a course about Mars and the Moon, students looked at the Moon through telescopes I set up for them, and later joined me on a guided tour of the National Air and Space Museum. Students have told me that these experiences were among the highlights of their undergraduate education. They made tangible the otherwise abstract ideas we discussed in class.

Major assignments in my courses reflect my commitment to iterative, student-driven learning. In many of my courses, students need to choose a topic, find relevant sources, and then develop an annotated bibliography to begin the process of writing their final papers. After receiving feedback on those bibliographies, they develop a rough draft and, for advanced undergraduate or graduate courses, submit the draft not only to me but also to a fellow student. In these more advanced courses, students give brief presentations that constructively criticize the work of a peer, who then has an opportunity to respond. I moderate this exchange, highlighting particularly helpful criticisms or especially convincing responses. Students give their written criticisms to one another, and I return their rough drafts with my suggestions for revision.

Students draw on my recommendations and those of their peers to complete their final drafts. This draft is often the product of more than a month of work, which means that it usually represents the very best effort of students working at the limit of their capabilities. In my opinion, this is how students truly improve their abilities as writers, researchers, and critical thinkers entering a world of looming environmental crisis.

Major assignments in my courses reflect my commitment to iterative, student-driven learning. In many of my courses, students need to choose a topic, find relevant sources, and then develop an annotated bibliography to begin the process of writing their final papers. After receiving feedback on those bibliographies, they develop a rough draft and, for advanced undergraduate or graduate courses, submit the draft not only to me but also to a fellow student. In these more advanced courses, students give brief presentations that constructively criticize the work of a peer, who then has an opportunity to respond. I moderate this exchange, highlighting particularly helpful criticisms or especially convincing responses. Students give their written criticisms to one another, and I return their rough drafts with my suggestions for revision.

Students draw on my recommendations and those of their peers to complete their final drafts. This draft is often the product of more than a month of work, which means that it usually represents the very best effort of students working at the limit of their capabilities. In my opinion, this is how students truly improve their abilities as writers, researchers, and critical thinkers entering a world of looming environmental crisis.

Courses I've taught (as of Spring 2021)

Georgetown University:

Course Instructor. Designed and taught revised seven-week module, “Global Warming: Causes, Consequences, and Controversy,” (Spring 2021, half-term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught revised seven-week module, “The Little Ice Age: Volcanoes and Crises in the Premodern World,” (Spring 2021, half-term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught course, “Neighboring Worlds: Moon, Mars, Venus, and Asteroids in History,” (Fall 2020, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught revised seven-week module, “Global Warming: Causes, Consequences, and Controversy,” (Spring 2020, half-term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught revised seven-week module, “The Little Ice Age: Volcanoes and Crises in the Premodern World,” (Spring 2020, half-term).

Course Instructor. Co-designed and co-taught course, “HyperHistory,” (Spring 2020, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught course, “Ancient Climate Changes,” (Spring 2019, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught revised seven-week module, “Global Warming: Causes, Consequences, and Controversy,” (Spring 2019, half-term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught revised seven-week module, “The Little Ice Age: Volcanoes and Crises in the Premodern World,” (Spring 2019, half-term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught graduate tutorial, “Introduction to the Dutch Golden Age,” (Spring 2018, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught two seven-week modules, “Global Warming: Causes, Consequences, and Controversy,” (spring 2018, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught course, “Mars and the Moon in Science, Science Fiction, and Society,” (spring 2018, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught graduate course, “The Environmental History of the Little Ice Age,” (fall 2017, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught two seven-week modules, “The Little Ice Age: Volcanoes and Crises in the Premodern World” (fall 2017, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught course, “The History of Humanity on a Changing Planet,” (fall 2016, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught course, “The Making of the Modern World,” (fall 2016, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught course, “Anthropocene: The History of Earth Under Human Dominion,” (spring 2016, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught course, “Warfare in Early Modern Europe,” (spring 2016, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught course, “A Global History of Climate Change,” (fall 2015, one term).

York University:

Course Instructor. Designed and taught online course, “Europe and the Natural World Until 1800,” (summer 2015, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught course, “Warfare in Early Modern Europe,” (2013-2014, two terms).

Teaching Assistant. “Medieval and Early Modern Europe,” (2012-2013, two terms).

Teaching Assistant. “Medieval and Early Modern Europe,” (2011-2012, two terms).

McMaster University:

Teaching Assistant. “Europe from the French Revolution to the End of the Second World War,” (2008, one term).

Teaching Assistant. “The Society of Greece and Rome,” (2007, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught revised seven-week module, “Global Warming: Causes, Consequences, and Controversy,” (Spring 2021, half-term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught revised seven-week module, “The Little Ice Age: Volcanoes and Crises in the Premodern World,” (Spring 2021, half-term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught course, “Neighboring Worlds: Moon, Mars, Venus, and Asteroids in History,” (Fall 2020, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught revised seven-week module, “Global Warming: Causes, Consequences, and Controversy,” (Spring 2020, half-term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught revised seven-week module, “The Little Ice Age: Volcanoes and Crises in the Premodern World,” (Spring 2020, half-term).

Course Instructor. Co-designed and co-taught course, “HyperHistory,” (Spring 2020, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught course, “Ancient Climate Changes,” (Spring 2019, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught revised seven-week module, “Global Warming: Causes, Consequences, and Controversy,” (Spring 2019, half-term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught revised seven-week module, “The Little Ice Age: Volcanoes and Crises in the Premodern World,” (Spring 2019, half-term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught graduate tutorial, “Introduction to the Dutch Golden Age,” (Spring 2018, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught two seven-week modules, “Global Warming: Causes, Consequences, and Controversy,” (spring 2018, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught course, “Mars and the Moon in Science, Science Fiction, and Society,” (spring 2018, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught graduate course, “The Environmental History of the Little Ice Age,” (fall 2017, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught two seven-week modules, “The Little Ice Age: Volcanoes and Crises in the Premodern World” (fall 2017, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught course, “The History of Humanity on a Changing Planet,” (fall 2016, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught course, “The Making of the Modern World,” (fall 2016, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught course, “Anthropocene: The History of Earth Under Human Dominion,” (spring 2016, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught course, “Warfare in Early Modern Europe,” (spring 2016, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught course, “A Global History of Climate Change,” (fall 2015, one term).

York University:

Course Instructor. Designed and taught online course, “Europe and the Natural World Until 1800,” (summer 2015, one term).

Course Instructor. Designed and taught course, “Warfare in Early Modern Europe,” (2013-2014, two terms).

Teaching Assistant. “Medieval and Early Modern Europe,” (2012-2013, two terms).

Teaching Assistant. “Medieval and Early Modern Europe,” (2011-2012, two terms).

McMaster University:

Teaching Assistant. “Europe from the French Revolution to the End of the Second World War,” (2008, one term).

Teaching Assistant. “The Society of Greece and Rome,” (2007, one term).